[ad_1]

One of the best ways to boost the health of your gut microbiome (the bacteria living in your intestines) is to eat foods that contain soluble fiber. Although humans lack the enzymes to digest these large carbohydrate molecules, the bacteria that live in our guts rely on them as their primary food source. Diets that are high in fiber support a healthy and diverse gut microbiome. And, as we’re learning, a healthy microbiome is essential to a healthy body.

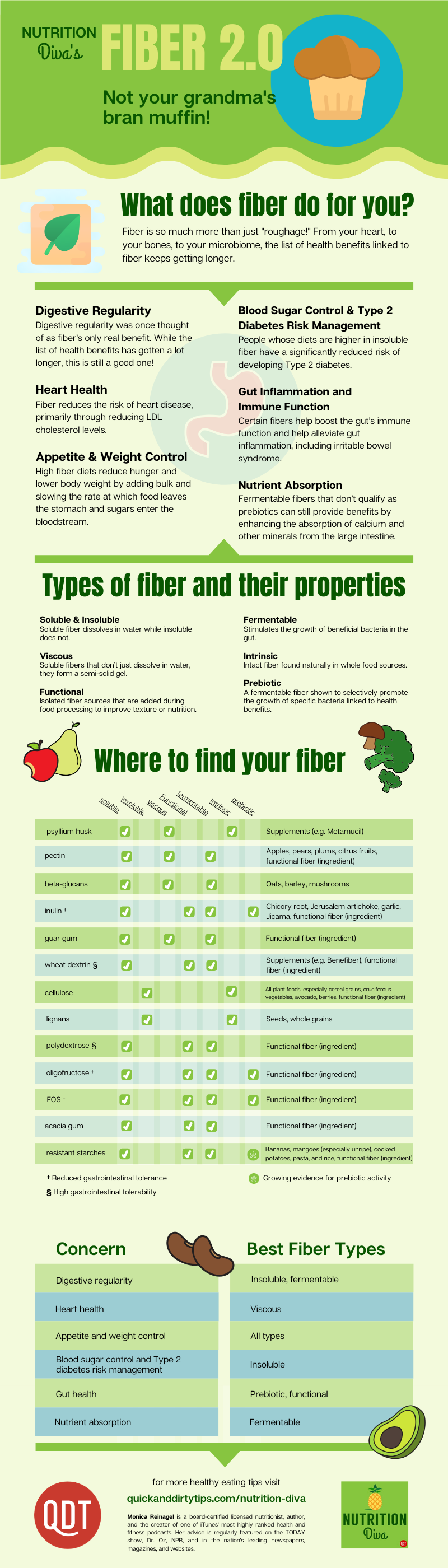

There is already an impressive list of benefits associated with a higher fiber diet—including appetite control, weight management, digestive health, and improved immune function. Prebiotic foods can also help improve the absorption of minerals and other nutrients—and may play an important role in building strong bones early in life and preventing bone loss later in life.

Prebiotic vs Fiber

First, just a quick clarification on the terms I’m using. It’s easy to mistake prebiotic as just another word for fiber. But the two terms are not exactly synonymous. All prebiotics are types of fiber but not all fibers are prebiotic. The term “prebiotic” is reserved for fiber sources that have been shown to selectively promote the growth of specific bacteria linked to health benefits.

Inulin, which is found in chicory root, sunchokes, onion, garlic, and leeks, is one of the more common prebiotic fibers. And although they have not yet been officially classified as prebiotics, there’s growing evidence that resistant starches have prebiotic activity. Resistant starches are found in bananas and mango (especially when they are underripe) as well as potatoes, pasta, and rice that have been cooked and then cooled.

(See below for an infographic of the different types of fiber and their benefits.)

How do prebiotics boost bone health?

You already know that calcium is critical to building and maintaining strong bones—which is why it’s important to make sure that your diet supplies enough calcium. This is especially critical during the teen and young adult years when your body is most rapidly building bone tissue. Ironically, this is also the age group most likely to fall short in their calcium intake.

After the age of 30 or so, we start to gradually lose bone mass and density and these losses accelerate for women following menopause. Keeping calcium intake up in the second half of life can help slow these losses and reduce the risk of osteoporosis and fractures.

However, your body only absorbs a fraction of the calcium in your food—anywhere from 5 to 60%. Part of this is because calcium in foods is often tightly bound to other compounds that hinder absorption.

An acidic environment can help to break these bonds and release more calcium for absorption—and this is where prebiotic fibers come in. As these fibers are fermented by the bacteria in your gut, short-chain fatty acids are created. In fact, many of the health benefits attributed to fiber are actually due to these short-chain fatty acids—which are sometimes referred to as postbiotics.

Among their other activities, short-chain fatty acids lower the pH in the colon, and this helps to increase calcium absorption. Several studies—in both older and younger populations—have linked fiber and prebiotic intake with reduced bone loss and improved bone mineral density. (See Sources, below, for links to the research.)

Interestingly, the amount of short-chain fatty acids produced in the gut is partially determined by your genetics. Some studies have found that the benefits of prebiotic intake on bone health depend in part on your genetic makeup. We’re not at a point yet where we can fine-tune fiber recommendations based on these genetic variations, but who knows what the future may hold?

See also: Can Genetic Testing Reveal Your Ideal Diet?

Of course, even with prebiotics on board to help with absorption, you still need to make sure that your diet is providing enough calcium. And, as with virtually every other nutrient, it’s best to get as much of your calcium as you can from foods rather than supplements.

Best food sources of calcium

Dairy products are a good source of absorbable calcium, with each 8 oz serving of milk or yogurt providing about a third of your daily requirement. But you can get all the calcium you need even if you are dairy-free. Other good sources of calcium include canned fish, tofu, and vegetables from the cabbage family, including broccoli, kale, bok choy, cabbage, mustard, and turnip greens. A half cup of Chinese cabbage or a cup of bok choy provides almost as much absorbable calcium as a glass of milk! Cabbages and leafy greens are also good sources of folate and vitamin K, nutrients that also help build strong bones.

See also: Diet for Healthy Bones

How much calcium do you really need?

The recommended intake for calcium is 1000 mg a day for adults. Adolescents, women over 50, and men over 70 need about 1300 mg. To get a rough estimate of how much calcium you’re getting:

- Start with 250 milligrams as your baseline. (The typical American diet provides about 250 mg a day, not counting dairy products.)

- Add 250 mg for each serving of dairy, canned fish, tofu, Chinese cabbage, or calcium-fortified nondairy milk or orange juice.

- Give yourself another 100 for any other cabbage family vegetables.

It’s not important that you get exactly 1000 mg of calcium every day—if it’s averaging out to your recommended intake, you’re probably getting all the calcium you need. If despite your best efforts, you aren’t quite meeting the requirements, consider taking a calcium supplement. But there’s no need to overdo it with a pill containing 1000 mg or more of calcium.

Although you definitely want to be sure to get enough calcium, more is not better. Excessive calcium intake can lead to kidney stone formation in people who are susceptible and high doses of calcium may increase the risk of heart attack for older women.

If you are taking a calcium supplement, I suggest taking only enough to close the gap between the recommended intake and what your diet provides on a typical day. For most people, that’s no more than 250 to 500 mg. However, this is not meant to replace the advice of your own physician. If your doctor has recommended a calcium supplement, check with them before changing your dosage.

Regardless of where you’re getting your calcium, remember that fiber—especially prebiotic fibers—can help you get the most out of it.

Guide to types and benefits of fiber

Share this Image On Your Site

[ad_2]